A 'just transition' for the Philippine's manufacturing sector

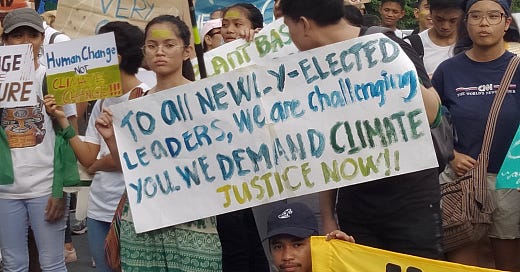

As the government begins to push towards green development and a ‘just transition’ towards climate resiliency, the lack of strong labor laws and safety nets for workers threaten to impede efforts.

Florence Galang is one of the many industrial workers in the city of Santa Rosa, Laguna. Santa Rosa is part of the province’s ‘industrial belt’, and is home to the province’s largest industrial park, Laguna Technopark. On the whole, Laguna is one of the country’s largest manufacturing bases, home to over 800 manufacturing firms and 21 industrial parks.

For five months from November 2021 to March 2022, Galang worked as a production operator at the Futaba Corporation of the Philippines, a semiconductor company in Laguna Technopark. As an agency hire, she had a contract making the provincial minimum wage of PHP 400.00 (USD 7.55) per day. Most of her wages went towards daily needs for herself, her mother, and her younger sister, while the rest went towards paying bills and rent.

Meanwhile, estimates from government agencies and independent research groups peg the family living wage as ranging from PHP 25,000 (PHP 472.00) to PHP 42,000 (USD 792.96) a month - a far cry from what workers like Galang are making.

The Philippines remains one of the ten worst countries in the world in upholding workers’ rights, according to the International Trade Union Confederation. According to Liga Para sa Regular na Hanapbuhay (LIGA), an organization of contractual workers, despite orders from the Department of Labor and Employment, at least 3,927 workers are still waiting to be regularized in Laguna alone. Some of the pending cases go as far back as 2016.

Low wages and contractualization remain deep-seated problems for Filipino workers. As the government begins to push towards green development and a ‘just transition’ towards climate resiliency, the lack of strong labor laws and safety nets for workers threaten to impede efforts in the manufacturing industry.

Greening the Philippine manufacturing industry

In 2016, the Benigno S. Aquino III administration enacted the Green Jobs Act, with the intention of affirming “labor as a primary social economic force in promoting sustainable development,” the protection of workers’ and people’s rights “in accord with the rhythm and harmony of nature.” The previous year, the Promotion of Green Economic Development Project (ProGED) outlined a roadmap to address the Philippine manufacturing industry’s challenges in industrial development and “integration [to the] ASEAN Economic Community,” effectively “greening the Philippine manufacturing industry.”

ProGED’s aim is to foster “Green Economic Development” - a combination of economic milestones to ensure global competitiveness and environmental sustainability. It lays down targets that the manufacturing industry should achieve by 2030, in areas of energy and resource efficiency, international standards, innovation, resource management, and foreign investment.

In particular, this means creating what is essentially a “green industry and service sector,” through a mix of developing existing systems and developing new ones. The ProGED roadmap imagines a Philippines at the forefront of green innovation capacity, leading ASEAN in resource productivity, utilization of renewable energy, and the implementation of systems in place for climate resiliency. This in turn would create an environment “highly attractive to foreign investment,” something ProGED emphasized is a “driving force” in Green Economic Development.

The Green Jobs Act was the first step in realizing these milestones. Since then, the Philippine government has laid down the foundations for shifting towards climate resiliency, including the creation of a Climate Change Commission as a policy-making body, implementing rules for the Green Jobs Act, and partnerships with the International Labor Organization (ILO) in implementing its Guidelines for Just Transition.

More recently, policymakers from above have tried to push for a “People’s Green New Deal” last November 2019, which calls for the establishment of mechanisms meant to drive green development. One of its goals is to establish a National Industrialization Council, with the mandate of laying out strategic decisions for “developing sustainable Filipino industrial enterprises.” It also seeks to develop science and technology, promote Filipino industries, review foreign investment and trade agreements, among others.

The COVID-19 pandemic also provided the Philippine government with a much-needed push to focus on green recovery. Data from the World Economic Forum states that the Philippines has spent some USD 3.11 trillion towards recovery and pandemic response; of which USD 970 billion has gone towards policies that are meant to shift the country towards a more sustainable climate. These include the adoption of an Enhanced National Greening Program, agroforestry development in watershed areas, and the implementation of work-from-home arrangements.

A ‘whole-of-government’ approach

From June 2016 to June 2018, ILO tested its just transition program in the Philippines, partnering with government agencies, workers, and employers’ organizations with the aim of starting the process of “structural change towards a sustainable, low carbon, climate-resilient economy.”

The result is the creation of a national strategy to “promote green decent work” and “tackle transitional issues in particular sectors,” including capacity building and market adjustments. Since then, the Philippine government has pushed towards the use of technology and the strengthening of the tech sector, including the recent passage of amendments to the Foreign Investments Act allowing for full foreign ownership of tech start-ups, among other provisions.

The ILO also recommended a push towards tech for the manufacturing sector, focusing on digitalization as a path towards “promoting competitive industries and reskilling workers.”

However, not all groups are on board. Alyansa ng Manggagawa sa Probinsya ng Laguna (ALMAPILA), a workers’ organization in the province, counters that the government’s recovery plans “could just as easily entice foreign encroachment in our industries and the creation of cheap and docile labor” if it is not coupled with a “solid plan for national industrialization and the protection of workers’ rights.”

Red Clado, ALMAPILA’s spokesperson, also stressed that vocational and reskilling programs “create a workforce tailored for industrial needs, instead of equipping Filipinos to solve problems.” For Clado, the manufacturing sector’s top priority should be to “provide job security and a livable wage for [its] workers.”

Manufacturing and foreign investments

By far the most crucial factor for the manufacturing industry and its goals of green development lies in foreign investment. In the first quarter of 2022 alone, approved foreign investments entering the country totaled PHP 8.98 billion (USD 171.43 million), 57.4% of which went towards projects and corporations within manufacturing. In total, foreign investments in manufacturing account for roughly one-fifth of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product.

This is part of longstanding government policy to focus on neoliberal, foreign investment-driven economics since at least the 1970s. From 1980 to 2020, foreign direct investment stock increased from USD 1.3 billion to USD 103.2 billion, or 29.9% of the nation’s GDP.

Who benefits from the influx of foreign investment? From the end of 2021 to May 2022, the manufacturing sector’s purchasing managers’ index (PMI) grew from 51.8 to 54.1, indicating a general increase in growth and investment. Last 2021, the semiconductor industry alone accounted for 41.2% of all exported goods in the Philippines, despite threats of COVID-19 hampering production.

But research think-tank IBON contends that most manufacturing firms in the country are “low value-added firms taking advantage of government subsidies and fiscal incentives.” The firm pointed out that foreign investments do not contribute to long-term Philippine development. “The country’s industrial base,” they said, “has only become shallower and more import-dependent.”

IBON calls existing policy a “destructive foreign investment fetish,” noting that foreign policy does not translate to domestic expansion, technology transfer, or efficient resource management. In the worst case, lax policies in foreign ownership and liberalization led to environmental destruction, citing a doubling of mineral exports between 2016 to 2018, from USD 2.35 billion to USD 4.04 billion, at the cost of “[depleting] resources for the country’s future industrial development.”

Community-level efforts

More work needs to be done. At the community level, workers aren’t familiar with concepts like just transition and green development. ILO noted this in their assessment of their pilot program in the Philippines, calling it “one of the biggest challenges the policy-making agencies are trying to surmount.”

For Galang, her priorities remain living wages and job security. “I hope corporations start taking care of the environment,” she said when asked about the idea of green recovery, “but what’s more important to me right now is that I make a decent living.”

Galang has since left Futaba, calling it a “dead-end job.” Working for an agency meant having no benefits like sick leave or vacation leave, and no hope of regularization. Currently she works at NHK Spring Philippines, also in Laguna Technopark, which makes hard disk drives and automotive parts. At NSP, Galang is a direct hire, which meant that she stood a chance of getting regularized after six months.

Her earnings, however, haven’t changed. She still makes the provincial rate of PHP 400.00. Price hikes in oil and other basic goods also meant that she now has to contend with an increasingly tight budget. “I spend 150 pesos on commuting alone,” she remarked. DOLE is set to increase wages in CALABARZON by PHP 47.00 (USD 0.88), effective July 15, but ALMAPILA says that it cannot offset the price hikes in the region.

Clado, meanwhile, remains hopeful. “There is a great opportunity for us to move forward with green development while securing basic workers’ rights,” he said. “But it cannot happen unless we start putting workers first before capital.”